by Bill Sardi

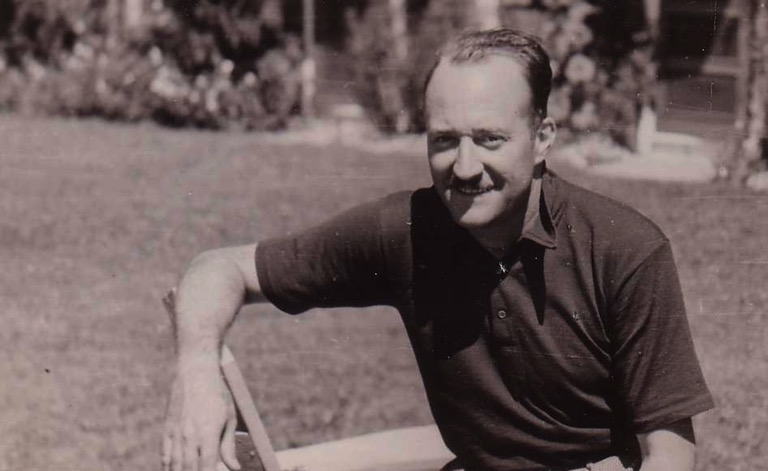

While Wall Street awaits the entry of over 1,813 new cancer drugs into human clinical trials representing billions of dollars of investment capital, the announcement of a bona fide cure for cancer comes from an outsider – patient Joe Tippens.

An astounding report of Mr. Tippens’ cancer cure is circulating the internet now. First diagnosed with small cell lung cancer in 2016 and with tumors popping up on scans in virtually every organ in his body, in desperation Joe Tippens began using a dog de-worming agent at the suggestion of a veterinarian.

He was told this cancer cure “was batting 1,000 in killing different cancers.” He heard one of the scientists involved in the research was cured. He had no time to dither. He was weeks away from dying.

Treatment began in the third week of January 2017. Three months later at MD Anderson Cancer Hospital in Houston, Tippens anxiously awaited the report of his oncologist who had no idea Tippens started taking the dog deworming medication.

The doctor is reported to have walked up to Mr. Tippens and said: “I am going to have to ask you to leave this hospital, because we only treat patients with cancer here at MD Anderson.”

Within just 3 months his cancer vanished. His insurance company spent $1.2 million before Tippens switched to a $5 a week medicine that saved his life. Daily vitamins and CBD oil were also an essential part of his curative regimen. Here’s the video report.

Don’t think Big Pharma isn’t involved here. Merck Animal Health division makes the de-worming drug that has gone up in price since the report of Tippens’ cure spread in the news media.

Joe Tippens now reports at his own “My Cancer Story Rocks” blog site that is bustling with visitors.

He now says around 40 otherwise hopeless cancer patients have reported similar cures.

He continues to take the anti-worming medication and dietary supplements as prevention.

His dietary supplement regimen that he still adheres to is as follows:

- Vitamin E complex (tocotrienols, tocopherols)

- Curcumin (turmeric extract 600 mg/day

- CBD oil

The history of this cure

The anti-tumor therapy involves an anti-worming agent used for horses and dogs. It has been deemed to be safe by the Food & Drug Administration. Published studies involving this canine drug, fenbendazole, date back a couple of decades. There has been a lot of foot dragging over fenbendazole since it was unexpectedly reported to exhibit potent anti-cancer properties when combined with a vitamin regimen in laboratory animals in a study published in 2008.

Researchers reported that fenbendazole alone or vitamins alone did not alter the size or growth of implanted tumors in laboratory mice. But their combination produced a striking increase in activity of one type of white blood cell, neutrophils, resulting in a no-growth effect. There also was strong inhibition of a protein (hypoxia inducing factor) that induces hypoxia (absence of oxygen) which forces cancer cells to utilize sugar for energy rather than oxygen.

In the laboratory this drug/vitamin combo overcame treatment resistance as well.

Researchers were initially investigating fenbendazole because it was interfering with anti-tumor studies with other drugs.

Given that pinworms are a common problem in laboratories where mice are employed in pre-clinical testing of anti-cancer drugs, use of fenbendazole to clear these animals of parasites is standard practice.

Unexpectedly, fenbendazole halted the growth of implanted human lymphoma cells in rodents.

To prevent animal infection during the testing period the chow fed to these lab animals is sterilized and then vitamins and minerals (vitamin A, D, E, K and B) are added back to eliminate variance in nutrient intake. But the chow for these lab animals in question was not sterilized and therefore more nutrients were delivered to these animals than normal.

Whereas implanted tumors take hold and grow 80-100% of the time, in this experiment none of the implanted tumors grew among 40 animals over a 30-day period! This was striking.

In 2011 researchers investigated fenbendazole for its ability to treat a nasty form of brain cancer (glioblastoma multiforme). Five-year survival with this form of brain cancer is only 10%. Over 600 clinical trials for this form of cancer have been unsuccessful in finding a cure. These researchers found the addition of an anti-worming (pinworm) agent (fenbendazole) halted the growth of brain tumors whereas among animals that were not de-wormed, there was consistent tumor growth. The researchers noted the long track record of safety for fenbendazole as well as its low cost and availability.

Contrarily, in 2013 researchers reported they found no evidence that fenbendazole has value in cancer therapy and did not warrant further testing.

Then in 2018 researchers in India reported fenbendazole exerts cancer cell killing activity at very low concentrations and does so partially by its inherent ability to inhibit the uptake of sugar (glucose) into fast-growing tumor cells. Cancer cells develop an inordinate demand for sugar to feed their growth, switching from oxygen to sugar as a source of energy. Fenbendazole did this by inhibition of an enzyme called hexokinase.

Fenbendazole’s ability to preferentially kill of malignant cells without harming healthy cells is another of its proposed properties.

The last thing the cancer industry needs is a cure

The last thing the cancer industry needs is a cure. In fact, it can’t afford a cure.

Financial analysts admit “a cancer cure is not a sustainable business model.”

Do you find these posts helpful and informative? Please CLICK HERE to help keep us going!